‘Artesia’s astronaut,’ Edgar Mitchell, dies at 85

Mere hours from the 45th anniversary of his historic moonwalk, the last surviving member of the Apollo 14 crew and “Artesia’s astronaut,” Edgar Dean Mitchell, died at the age of 85.

The young man most knew from an early age was destined to leave his mark on the world did just that in 1971 as the lunar module pilot of the three-man Apollo 14 mission. Also on crew were mission commander and veteran astronaut Alan B. Shepard and command module pilot Stuart Roosa.

The trio landed on the moon on Feb. 5, 1971, where Mitchell and Shepard performed two successful walks, gathering samples and information that proved invaluable to scientists seeking to gain a broader understanding of the moon’s origins.

They returned Feb. 9, 1971, to a hero’s welcome, with Mitchell and Shepard taking their place in history as two of just 12 individuals to set foot on the moon.

But before that, Mitchell was an Artesia Boy Scout, a member of the Bulldog basketball team, and a young man with a dream.

Born Sept. 17, 1930, in Hereford, Texas, Mitchell moved as a boy with his family – father Jay, mother Ollidean, sister Saundra Jo, and brother Jay – to 609 Dallas Ave. in Artesia, and he thereafter considered the community his hometown.

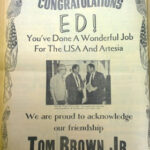

Recalled by some as quiet, somewhat shy, but exceedingly intelligent in his youth, some of the closer friendships Mitchell formed in Artesia remained with him throughout his life, including that with longtime resident Tom Brown.

Brown and Mitchell became inseparable friends as boys, such that, as Brown puts it, “When it was bedtime, if one of us wasn’t home, our mother knew he was at the other’s house.”

The two shared a love of flying and, once they reached the necessary age, would take Brown’s scooter to the Artesia Airport to train as flight students.

“I still laugh that we both started flying at the same time,” says Brown. “I tell people there wasn’t a heck of a lot of difference – I got a private pilot’s license, and he walked on the moon.”

Mitchell graduated from Artesia High School in 1948 at the top of his class and earned a Bachelor of Science in Industrial Management from the Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1952. The following year, he entered the U.S. Navy, where he flew A3 aircraft for Heavy Attack Squadron Two and also served as a research pilot and chief of the Project Management Division of the Navy Field Office for Manned Orbiting Laboratory.

Following a year in the Aerospace Research Pilot School, where he graduated first in his class, Mitchell served as an instructor in advanced mathematics and navigation theory for astronaut candidates before being selected in 1966 as an astronaut by NASA.

The $400 million Apollo 14 mission launched Jan. 31, 1971, and dropped into orbit 10-and-a-half miles above the moon on Feb. 4. They were to be the first to land in the moon’s lunar hills, which they eagerly viewed that day from their craft.

Mitchell noted the stark difference in lighting made it look “like you could walk along that surface and fall into nothing, absolutely nothing.”

Orbiting at 53,600 feet above the lunar peaks, Mitchell proclaimed, “We’re here!” to ground control before noting, “This country down here is really rugged at this altitude. That’s the most stark, desolate-looking piece of country I’ve ever seen. We could be 500 feet in the air the way this terrain looks. It’s really deceiving. It’s good to hear you say we’re that high.”

In 1971, the world watched – this time in living color – as Mitchell and Shepard stepped onto the moon’s surface for their first of two walks. Their primary objective was Cone Crater, 4,000 feet east of their landing site, where scientists believed lay vehicle-sized boulders blasted out of the moon’s surface by meteors billions of years prior.

Their safe landing was welcome news to their family and friends on Earth. The Associated Press reported Mitchell’s eldest daughter, Karlyn, then 17, ran outside to run up the American flag while sister Elizabeth, 11, the anxiousness over, fell asleep over a bowl of cereal.

With Mitchell joking, “I think they put champagne instead of iodine in the LEM water this time,” the two astronauts danced along the surface, acclimating themselves to the conditions, before settling down to work. They succeeded in collecting 109 pounds of rock samples and erecting a $25 million science station before the time came to return to the ship – but not before a last bit of fun.

Shepard and Mitchell had previously planted an American flag on the moon’s surface, and Mitchell’s photo of Shepard standing beside it, his own shadow visible at the bottom of the shot, has been dubbed the first “astronaut selfie.”

As they prepared to board the craft, Shepard produced a makeshift golf club he’d formed from the handle of a digging tool and a six-iron head he’d brought on the journey. He produced a golf ball and took a one-armed swing.

“You got more dirt than ball that time,” Mitchell noted.

Shepard swung again, this time launching the hovering ball on a journey of untold miles.

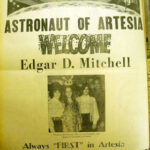

Mitchell’s first several days after returning to Earth were occupied by visits with top-ranking politicians and dignitaries, but once the whirlwind slowed, there was one place in particular he wanted to go: Artesia.

He arrived here March 14, 1971, to a red carpet rollout from the Artesia Trailblazers, and headed straight to the home of his childhood friend, Brown.

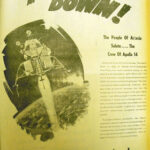

That day’s edition of the Artesia Daily Press was awash in photographs, articles and advertisements celebrating the return of the hometown hero, as well as a statement from Mayor J.L. Briscoe proclaiming March 15, 1971, Edgar D. Mitchell Day.

That day’s edition of the Artesia Daily Press was awash in photographs, articles and advertisements celebrating the return of the hometown hero, as well as a statement from Mayor J.L. Briscoe proclaiming March 15, 1971, Edgar D. Mitchell Day.

“He has brought much pride to the people of Artesia,” the proclamation noted.

Mitchell spent the next morning speaking in shifts to each grade of students in the Artesia Public Schools system, along with students from the College of Artesia.

He is remembered as an inspiration to many of the youth who met him that day and took particular care to encourage them to achieve their own dreams. Upon receiving a “Most Outstanding Citizen of Artesia” award, he stated, “You do me great honor. However, with the young people that I have seen fill the high school auditorium three times today, I have no doubt that when record are broken, it doesn’t take very long to set new ones.

“I am looking with great hope to the young people of Artesia that before very long, you can hand out more of these (awards) to some of you. I am sure that anything I have done, they will exceed sometime in the future.

“The thing we need most for our young to understand is perspective. We have to view the world as a large community. To succeed, we must have a sense of values and desire to achieve a oneness.

“Artesia is a great community, and I am very proud that I have grown up here.”

Mitchell had intended to plant a Bulldog flag on the moon’s surface but regretfully informed the students of Artesia High School some of the flag’s components had been deemed a fire hazard by NASA. The students weren’t disappointed in the least, cheering wildly as he presented the school with an Apollo 14 patch and American flag that had made the voyage to the moon.

Mitchell also attended a dedication ceremony for the establishment of the Edgar D. Mitchell Highway, a portion of U.S. 285 running from the outskirts of Carlsbad through Artesia to the edge of Roswell. He stated he was humbled and lightened the mood by asking whether he would be “allowed to speed” down the stretch of roadway or possibly “set up a toll booth.”

A parade down Main Street that afternoon ended at Bulldog Bowl, where Mitchell addressed the community. As he expressed many times in his life, his voyage had left him changed, and the man who stood before his hometown was no longer quiet nor shy but passionate in his newfound understanding of mankind’s place in the universe.

“We can’t afford war,” Mitchell told the assembly. “We can’t afford having people be hungry. We can’t afford to continue to pollute our environment. When I was in space, when you look back at the earth and see how small it is and think that it is the only hope we have … it is a small home, and it is a closed system. In other words, we are not getting any more water, any more minerals, any more petroleum.

“If we are not careful, we are going to destroy it. You look back at the beautiful planet and say, ‘That is home.’ It is all we have got. Ladies and gentlemen, we must take that challenge. We must develop within ourselves a broad perspective of what we are on this planet and strive, each and every one of us, to solve the problems of brotherly love and living with our neighbors, outlaw war, and clean up our environment.”

Mitchell would go on to write three books over the years that also laid bare his desire to convey what he learned 238,900 miles above the world to the people in it.

In his 1996 work, “The Way of the Explorer,” Mitchell wrote, “You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it.

“From out there on the moon, international politics look so petty. You want to grab a politician by the scruff of the neck and drag him a quarter of a million miles out and say, ‘Look at that, you son of a bitch.’”

His old friend, Tom Brown, who went on to serve New Mexico as a state representative, took no offense. He understood Mitchell’s hope and was proud to escort him March 16, 1971, to a joint session of the New Mexico Legislature, where Mitchell addressed the representatives and senators, urging them to invest in science and to think of Earth as “a spaceship with limited resources.”

Mitchell’s death was reported Friday afternoon. He passed at 9:30 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 4, in West Palm Beach, Fla., from an undisclosed illness.

“He was an awfully good friend,” Brown said Saturday. “I’ve had several people we went to high school with call today to talk about him. I’ll miss him.”